Structural Reforms in East Asia The Key to Sustaining Global Recovery and Advancing Regional Free Trade

Julius Caesar Parrenas, PhD

Senior Advisory Fellow, Institute for International Monetary Affairs (IIMA)1

(posted from: http://www.iima.or.jp/pdf/newsletter2010/NLNo_37_e.pdf)

The recent G20 and APEC meetings in Seoul and Yokohama underscored the importance of structural reforms. While G20 leaders struggled over the way forward to achieve sustained global economic recovery, APEC leaders went ahead to launch work toward a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), possibly through the expansion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Embedded in the G20 and APEC leaders’ statements are references to a key issue that will influence the success of current efforts to sustain global recovery and advance free trade.

Annexed to the G20 statement is a document entitled the “Seoul Development Consensus for Shared Growth,” which laid out the framework for future work on “infrastructure, private investment and job creation, human resource development, trade, financial inclusion, growth with resilience, food security, domestic resource mobilization and knowledge-sharing.” The APEC statement referred to a strategy for achieving high-quality growth that is balanced, inclusive, sustainable, innovative and secure, described in detail in a separate document entitled “The APEC Leaders’ Growth Strategy.”

At the heart of this growth strategy is a renewed push for greater balance between domestic and external demand within economies, which is in turn key to addressing huge trade imbalances that have significantly contributed both to the current malaise afflicting the global economy and growing frictions over trade-related issues. This growth strategy hinges on structural reforms to address deep-seated problems that have emerged in the course of one of the longest periods of strong economic performance the world has ever seen.

Over the past two decades, the world economy doubled in size, driven by a threefold expansion of trade. This period of rapid growth eventually ended with the financial crisis, and the world now faces the prospect of prolonged economic malaise, if not a double-dip recession, as governments in most advanced economies grapple with anemic private demand, stubbornly high unemployment and unprecedented levels of public sector debt.

The failure of massive and globally coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus to quickly bring about economic recovery underscores the reality that the problems of today’s global economy are rooted in structural imbalances. Previous years’ rapid economic growth relied on unsustainable levels of consumption in rich economies, supported by asset bubbles that encouraged consumers to splurge on credit.

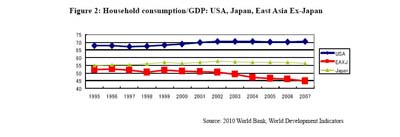

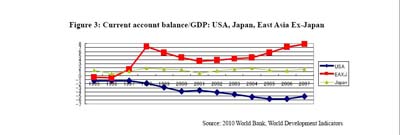

From 1990 to the eve of the crisis in 2007, liabilities of US households and non-profit organizations grew by US$10.7 trillion, with home mortgages (including loans made under home equity loans secured by junior liens) and consumer credit making up 92% of the total. Borrowing helped finance an unprecedented expansion of household consumption in the US, which increased its ratio to GDP from an already high level of 67.8% in 1995 to 70.7% in 2007. As imports soared, the US current account deficit swelled from 1% to 6% of GDP.

To meet this burgeoning demand, huge investments flowed into emerging markets’ export industries and supporting infrastructure. East Asia, where production networks were expanded in this process, reaped huge benefits. As their exports boomed and trade surpluses soared, the economies of the region’s emerging markets (East Asia ex-Japan2

In theory, trade imbalances are corrected as higher incomes and appreciating currencies boost consumption and imports in surplus economies, while the reverse occurs in deficit economies. Instead of increasing, however, East Asia’s household consumption declined as a fraction of GDP. A major portion of their huge surpluses were recycled back to fund the continued growth of demand in developed markets.

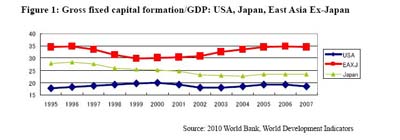

Figures 1-3 illustrate the development of economic imbalances across the Pacific before the crisis. Figures 1 and 2 very clearly contrast the developments in East Asia, where huge resources were increasingly channeled to investment in fixed assets, particularly after the Asian crisis, at the expense of consumption, and in the US, which provides a mirror image of this trend. Figure 3 shows the resulting trans-Pacific trade imbalance.

In the wake of the crisis, the combined impact of huge financial losses, layoffs and fiscal deficits are expected to constrain the growth of demand in advanced markets in coming years. What to do with the huge productive capacities that have been built up to satisfy these elevated levels of consumer demand has become a major problem. With governments facing growing constraints on further stimulus measures, more economic dislocations will result as these capacities are further scaled down.

The solution to restoring the world economy’s diminished growth potential to pre-crisis levels is an obvious one: accelerate the expansion of consumer demand in emerging markets. With its large population, rapidly growing economies and considerable savings, East Asia has the potential to become a major growth engine. However, realizing this potential would require significant structural reforms. This means raising consumption levels and accelerating the transfer of labor from low- to high-productivity sectors.

In calling for a more balanced pattern of global growth that is at the same time stronger and more sustainable, inclusive, innovative and secure, leaders of both the G20 and APEC are on the right track. Tight government budgets require concrete initiatives that can produce the most impact for every cent of taxpayers’ money. Such initiatives should be able to mobilize the huge resources available in the private sector.

They should also be mutually reinforcing to produce multiplier effects. An example of such a package would simultaneously aim to expand micro- and small businesses, stimulate infrastructure investment to support their growth, develop capital markets to help finance these investments and train officials to provide enabling regulatory systems. Some ideas developed by the private sector, international financial and development institutions and academic experts are as follows.3Financial inclusion. Providing financial access to the estimated 700 million people earning below the equivalent of US$2 per day in the region can have very significant impact on growth. In recent years, new technologies and innovations have boosted the commercial viability of microfinance, making it a more potent tool for financial inclusion. Governments can accelerate the wider adoption of these technologies and innovations by providing favorable policy environments.

Successful examples of reforms that spurred the expansion of mobile banking, point-of-sale technology and smart cards, and more effective use of state banks to increase financial access already abound. Providing effective regional platforms for the sharing of best practices and technical capacity-building can accelerate the flow of finance to millions of potential micro-enterprises.

SME finance. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) employ over 70% of people in most economies in the region. Various surveys indicate that access to finance is the most serious constraint they face, especially with respect to two key issues: credit information and legal frameworks for secured lending.

Governments can put in place credit information sharing systems that expand the types and sources of financial information on borrowers available to lenders, together with strong legal protections for data and consumers. Plugging gaps in legal frameworks to provide greater clarity and certainty to creditors will also help make more credit available to SMEs.

Infrastructure public-private partnership. The region needs infrastructure to spread development more evenly within and across countries. The ADB estimates that Asia will need $750 billion annually over the next ten years to meet its infrastructure needs. Private sector investment, which can contribute a significant portion, is hindered by various political and legal risks as well as uncertainty over future demand.

Governments and private sector need to come together to discuss how risks can be more effectively allocated. Multilateral and export credit agencies can also play a role in assuming certain risks and giving more comfort to private investors. A proposal by the APEC Business Advisory Council and the Advisory Group on APEC Financial System Capacity Building to set up an Asia-Pacific Infrastructure Partnership, a permanent regional forum for such dialogues, supported by technical expertise and sharing of best practices, would be a significant step forward.

Capital markets. Underdeveloped capital markets pose a major obstacle to the recycling of East Asia’s huge savings to fund infrastructure and business expansion. In spite of various fruitful initiatives such as the Asian Bond Market Initiative and the Asian Bond Fund, the region still lacks a large and diverse investor and issuer base, hindering the development of deep and liquid markets.

The establishment of separate securities markets for professional investors can increase corporate bond issuances, which are presently discouraged by stringent rules designed to protect retail investors. Barriers to cross-border settlement can be eliminated through coordinated action among officials and market players.

Bilateral arrangements to use foreign securities as eligible collateral can be expanded to increase trading of securities. A scheme can be introduced to expand the regional investor base, adapting Europe’s successful experience, where funds qualifying under a common set of guidelines, once approved in one jurisdiction, can be automatically sold in all participating markets.

Financial regulatory reform. Recent financial reforms have focused on strengthening regulations in response to excesses that led to crises in America and Europe. However, East Asian regulators must also be given the tools to help mobilize the region’s savings and expand financing for small enterprises and infrastructure and to accelerate the development of capital markets. This requires an effort to ensure that new global rules are supportive of these regional goals.

Regional institutions are needed to develop global standards that take into account East Asian market infrastructure and business models. Capacity-building is needed to help regulators obtain resources and authority to exercise effective supervision and implementation of rules. While there are ongoing regional efforts to promote these goals, a regional initiative supported by multilateral agencies, regional organizations and regulatory bodies can provide a much-needed impetus.

The recent APEC Finance Ministers’ Meeting in Kyoto has given explicit and very encouraging recognition to the ongoing work of the private sector, international bodies and public institutions in these five areas. The Ministers launched an APEC Financial Inclusion Initiative and initiated efforts to facilitate cross-border marketing of fund management services within Asia. They welcomed collaboration among private sector, multilateral agencies and export credit agencies to expand infrastructure PPPs in the region.

Finance Ministers also called on governments to collaborate with the private sector in producing initiatives to promote SMEs’ access to finance, including initiatives to improve credit information sharing systems and legal frameworks for secured lending. They committed to take action to help domestic regulators in the region implement financial reforms. Follow-up efforts will be needed to ensure that the foundations laid by the Finance Ministers in Kyoto will give rise to successful initiatives that can make significant contributions to structural reforms in coming years.

The crisis has reawakened dormant protectionist sentiments, which are now rearing their ugly heads in the face of continuing economic dislocations. Without a return to healthy economic growth, public pressures to protect domestic jobs and international conflicts over trade and currency policies are likely to intensify. The future of the global trading system and progress toward FTAAP will hinge on efforts to redress imbalances through East Asia’s transformation into a new engine of global growth.

For Japan, the stakes are high. It has become increasingly reliant on exports, which has been the largest contributor to GDP growth for most of the past decade, and even more so since the crisis. A mature economy and ageing population seriously limit the potential of domestic demand as a source of future growth. Japan’s best hope for continued prosperity lies in Asia, where it remains well positioned to leverage its production networks, technology and financial power to assume a central role in the emergence of a huge consumer market.

Japan assumed the chairmanship of APEC in 2010 under the motto of “change and action.” Japan’s leadership enabled APEC to plant the seeds of a future Asia-Pacific free trade area and stronger, more balanced and more sustainable growth. Making these seeds grow and bear fruit will indeed require bold policy changes by East Asian governments, including Japan, to embrace free trade with all its challenges, accompanied by concrete actions to undertake the needed structural reforms.

1The author is also Advisor on International Affairs at the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd

2Defined here as being composed of 9 economies, which include China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

3More detailed proposals are contained in the 2010 Report on Capacity Building Measures to Strengthen and Develop Financial Systems submitted by the Advisory Group on APEC Financial System Capacity Building, endorsed by ABAC and annexed to the 2010 ABAC Report to the APEC Finance Ministers. This report is available on the Advisory Group page of the ABAC website (https://www.abaconline.org/v4/download.php?ContentID=2609825).

Copyright 2010 Institute for International Monetary Affairs (IIMA). Posted with permission.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopy, without permission from the Institute for International Monetary Affairs.

Address: 3-2, Nihombashi Hongokucho 1-Chome, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0021, Japan

Telephone: 81-3-3245-6934, Facsimile: 81-3-3231-5422

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. URL: http://www.iima.or.jp

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://old.pecc.org/

Comments