Chapter 1 - Structural reforms as drivers of growth and inclusion

CONTRIBUTED BY MS. EDITH SCOTT AND PROF. MICHAEL ENRIGHT, ENRIGHT, SCOTT & ASSOCIATES SINGAPORE WITH ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTIONS FROM MEMBERS OF PECC

The Asia-Pacific is forecast to grow by 3.2 percent in 2015, the lowest level since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) before returning to what has become the ‘new normal’ growth of around 3.4 to 3.5 percent. Growth for both advanced and emerging economies in the region is significantly lower than before the crisis years, indicative of some the important structural changes taking place both within regional economies as well as in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole.

However, the aggregate numbers mask important divergences in the rates of growth among regional economies as well as headwinds to growth coming from volatility in financial and other asset markets. Foremost amongst these headwinds is a possible rise in US interest rates for the first time in almost nine years. That decision will be made on the basis of employment and inflation as per the Federal Reserve’s mandate but also with some due attention paid to the impact it would have on the global economy and the feedback that would have on the US economy.

Looking beyond the immediate next few months, the growth numbers also mask over fundamental structural changes taking place within the region’s economies. This includes a significant reduction in the role of trade as a driver of growth.

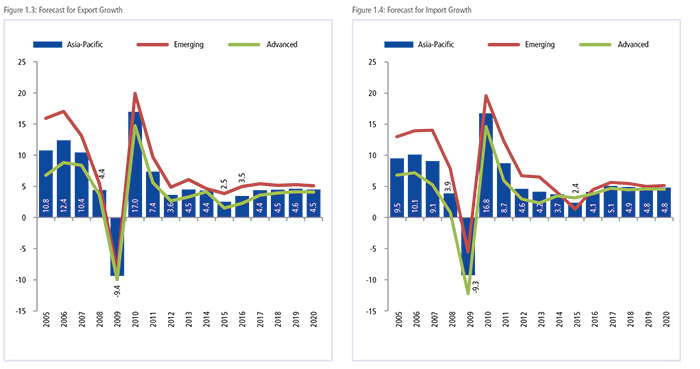

Since the GFC, with the exception of the rebound year of 2010, trade growth in the region has failed to take off and remains significantly lower than during pre-crisis years. This was largely expected in the wake of the weakness of demand from US consumers badly hit by the mortgage crisis but also continued by the Euro zone crisis and the impact that has had on consumption in Europe. However, even as the US economy has recovered, trade growth remains muted which raises the question of whether the slowdown is cyclical in nature or more due to structural changes taking place in the regional and global economies. One question is whether more global production is being ‘on-shored’ or ‘nearshored,’ that is, taking place closer to final destination markets – i.e. are global value chains getting shorter? Another question is whether technological and business innovations are again changing the shape of the chains.

STRUCTURAL CHANGES TO REGIONAL ECONOMIES

While the immediate post-crisis years were unusual in the distortions brought through the stimulus to sustain aggregate demand, the question is, when will the ‘new normal’ settle in a more predictable pattern? The current forecast is for reasonable but unexceptional growth for the region as whole with some economies growing faster. One common characteristic for the immediate post crisis period has been the reduction in the role that the external sector – net exports – play in the growth.

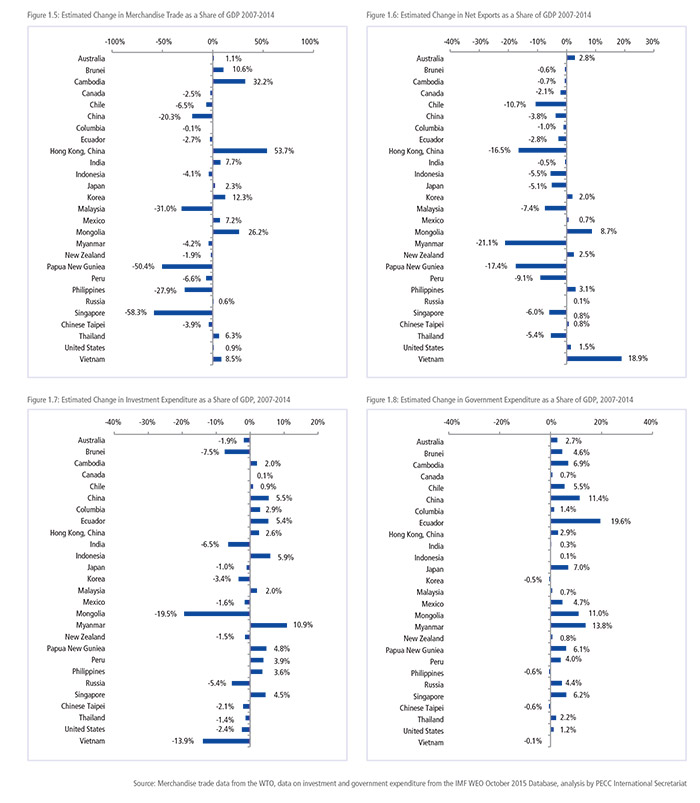

Figures 1.5 to 1.8 show the estimated changes in the shares of GDP of total merchandise trade, net exports of goods, investment and government expenditure. As seen in Figure 1.6, the share of net exports for most regional economies has fallen since the crisis, with much of the slack in demand taken up by an increased share of investment or government expenditure as seen in Figures 1.7 to 1.8.

If economies are to grow at faster levels than is currently forecast, with interest rates at historical lows and fiscal space limited, then significant structural reforms will be needed to stimulate that growth. Depending on the current structure of the economy different reforms are required – for example, for some it means continuing to shift aggregate demand from a reliance on investment to greater consumption, for others increasing investment, and across the board improvements to the efficiency with which those inputs – labor and capital – are put to use to increase productivity.

INITIATIVES TO BOOST GROWTH

For the first decade of the 21st century – the years 2000 to 2010 including the dot-com bust and the Global Financial Crisis, the size of the Asia-Pacific economy increased from US$20 trillion to about US$38 trillion growing at a rate of 6.3 percent a year. From 2010 to 2020, the Asia-Pacific economy is forecast to grow from US$38 trillion to US$62 trillion – an average growth rate of around 5.0 percent. These rough calculations demonstrate the drastic changes taking place in the region and the urgent need to rethink growth strategies. As a further illustration of the slowdown taking place, if the Asia-Pacific economy were to grow at the same pace from 2010 to 2020 as it did from 2000 to 2010 it would reach around US$70 trillion; in other words, the slower growth has resulted in a loss of around US$8 trillion.

Several initiatives are underway that could help to boost growth, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a China-led development bank with an initial capital of US$50 billion, is being established and on October 5th, 2015, 12 Asia-Pacific economies reached a deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations. The TPP, if ratified, is estimated to generate by 2025 nearly US$240 billion in income gains for its members. Negotiations are underway for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) among 16 East Asian economies that is estimated to generate by 2025 gains of around US$550 billion. At their meeting in Beijing last year, APEC leaders agreed to a roadmap for achieving an FTAAP that, if it included all APEC members, would lead to estimated gains of around US$2.5 trillion.

These amounts may sound impressive, but even if the benefits of the AIIB, TPP, RCEP, and an FTAAP are fully realized, they are a drop in the bucket compared to what is needed. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated that between 2010 and 2020, Asia’s overall infrastructure needs alone will be US$8 trillion. Increasingly, economies aspire to, and demand, growth that is sustainable and inclusive. This raises the very real question of where such growth will come from. Structural reforms are not new – economies worldwide have been implementing them for decades. Thanks to monitoring and research conducted by APEC and the OECD, among others, recent breakthroughs provide a new understanding of how structural reforms generate growth and new directions for the future. In September 2015, APEC Leaders agreed to endorse a five-year work plan through 2020 to promote balanced and sustainable growth and reduce inequality, embodied in the Renewed APEC Agenda for Structural Reform.

FROM TRADE REFORMS TO TRADE AND STRUCTURAL REFORMS

As tariffs, quotas and other trade barriers have fallen with trade liberalization, the focus of efforts to generate growth has shifted to structural obstacles that create behind-the-borders barriers to business. Structural reforms are changes in government institutions, regulations and policies designed create a business environment that supports efficient markets. The goal of structural reform is to bolster the strength and efficiency of markets in order to enhance living standards. When trade barriers fall, structural reforms become more important because they are necessary to support trade, which is cost and time sensitive and requires an efficient business environment. Entry into the WTO also has required new members to undertake structural reforms.

Boosting labor productivity is the leading way structural reforms drive economic growth. Labor productivity growth has been shown to account for at least half of GDP growth in most OECD members, often accounting for a much larger contribution. Structural reforms put into effect since the early 2000s have helped raise the level of potential GDP per capita by roughly 5 percent across countries on average, most of the gains stemming from higher productivity, according to the OECD. Analytical work by the OECD suggests that further reform along the lines of current best practice could boost the long-term level of GDP per capita by 10 percent across OECD members on average, which translates to an average gain of roughly US$3,000 per person.

In November 2014, the G20 in its Brisbane Action Plan committed to raise its collective GDP by more than 2 percent above the trajectory set forth in the IMF’s October 2013 World Economic Outlook (WEO). To this end, members submitted commitments to macroeconomic reform as well as structural reforms in product and labor markets, trade, and investment. The IMF and the OECD have found that the proposed reforms, if implemented fully, would raise the collective GDP of the G20 by more than 2 percent and contribute in excess of US$2 trillion to the world economy by 2018. Reducing inequality and promoting inclusiveness are also on the agenda.

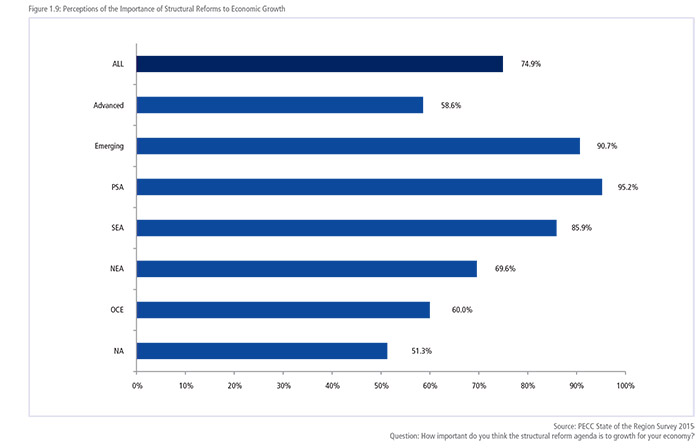

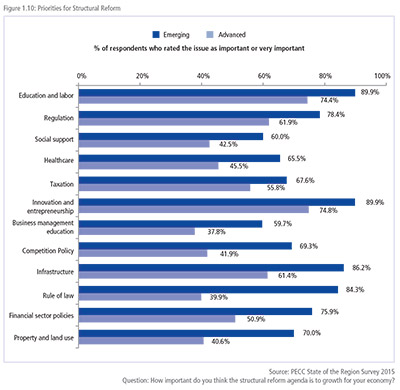

Since 2013, structural reform has accelerated in many emerging economies, while slowing in many advanced economies. Because labor productivity is the principal driver of growth in both advanced and emerging economies, the focus is on improving productivity through product market reform, in particular, through reforms in education and innovation policies. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, structural reform in general was reported as “important” or “very important” to the growth of their economy by over 90 percent of respondents from emerging economies, with innovation and entrepreneurship receiving an importance rating of nearly 90 percent. Among respondents from advanced economies, over 58 percent ranked structural reform as “important” or “very important” to growth, reflecting the more advanced state of their overall regulatory systems, while over 74 percent ranked structural reforms in “innovation and entrepreneurship” as “important” or “very important” to growth.

Across all economies, product market regulation, trade and foreign direct  investment still have room to generate growth. Advanced economies have been giving priority to these broad policy areas as well as public spending and tax systems. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, over 61 percent and 55 percent of respondents from advanced economies viewed structural reforms in regulation and taxation, respectively, to be "important" or "very important" for future growth. The corresponding percentages for respondents from emerging economies were 78 percent and over 67 percent.

investment still have room to generate growth. Advanced economies have been giving priority to these broad policy areas as well as public spending and tax systems. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, over 61 percent and 55 percent of respondents from advanced economies viewed structural reforms in regulation and taxation, respectively, to be "important" or "very important" for future growth. The corresponding percentages for respondents from emerging economies were 78 percent and over 67 percent.

Further reductions in barriers to trade and FDI are particularly important to integrate emerging economies into global value chains. When emerging economies win a foothold, they access world markets, technology, and high value added inputs. Their participation in global value chains, however, is vulnerable to tariffs and nontariff barriers. Gains are to be had from streamlining and modernizing customs procedures. Foreign direct investment can help emerging economies integrate into global value chains and improve productivity through access to technology and inputs.

RAISING PRODUCTIVITY LEVELS

In emerging economies, there are still substantial gains to be realized in freeing up major parts of the economy from the control of the state and state-owned firms. There also are major gains to be had in breaking down barriers to entry in the professional services, retail, transport, and communications sectors. Many emerging economies still face challenges with the rule of law, which is necessary for economic growth. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, 69 percent and 84 percent of respondents from emerging economies viewed structural reforms in competition policy and rule of law, respectively, to be “important” or “very important” for the future growth. “Rule of law” essentials include the guarantee of security of person and property, contract enforcement, and curbs on government power, capture and corruption.

Financial sector liberalization, which receives higher priority in emerging economies, has been moving ahead to improve the efficiency of capital allocation and growth potential remains to be tapped. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, nearly 76 percent and 51 percent of respondents from emerging and advanced economies, respectively, viewed structural reforms in financial sector policies to be “important” or “very important” for future growth. In emerging economies, there is ongoing need for prudential regulation and supervision to promote, among other things, the improved pricing of risk.

Some English-speaking advanced economies lag behind world leaders in productivity growth despite relatively high levels of investment in knowledge-based capital. In these economies, gains can be had by improving the efficiency and equity of compulsory education, removing barriers to domestic and foreign investment and promoting firm entry in services, and boosting efficiency in health care and state innovation programs.3 In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, 74 percent of respondents from advanced economies viewed “education and labor” as “important” or “very important” areas of structural reform for future growth, ranking second only to “innovation and entrepreneurship.”

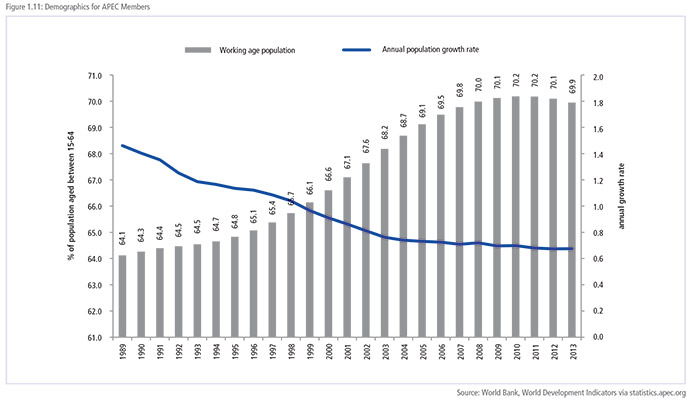

One issue that the Asia-Pacific will need to confront in terms of growth is the slowing population growth. The percentage of the region’s population at working age peaked at 70.2 percent in 2010 to 2011 with total population growth rate also flattening out. Advanced and indeed emerging economies with rapidly ageing populations face a different set of growth challenges. Reforms to unleash growth include reducing barriers to entry for domestic and foreign firms, rebalancing the tax systems, and boosting labor force participation to enable workers to work further into old age and to raise female employment rates.

Emerging-market economies have been giving priority to education and labor market policies to build up knowledge-based capital and skilled labor. Despite their progress in the past few decades, human capital policy priorities remain focused on strengthening children’s access to basic education. Areas where there are still large gains to be made, include improving physical access to schooling, school affordability including provision of free secondary school education, and higher quality teaching and teacher training. Improving tertiary education also is an important continuing policy priority. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, among respondents from emerging economies, 55 percent reported being “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied” with primary education, early education and child care, and 54 percent reporting the same for secondary and tertiary education.

IMPORTANCE OF VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Strengthening vocational education and training is another potentially powerful structural reform for emerging economies.6 In the Survey, over 73 percent of respondents from emerging economies reported being “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied” with the match between educational training and needs in their economy. Among respondents from advanced economies, over 55 percent were “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied” with the match between educational training and needs in the economy, followed by 51 percent reporting the same for cooperation between education providers and employers, the lowest satisfaction ratings among the labor and education issues for those economies.

RELIEVING INFRASTRUCTURE BOTTLENECKS

Relieving infrastructure bottlenecks is a key priority for boosting physical capital and labor productivity in the emerging economies. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, 86 percent of respondents from emerging economies viewed infrastructure reform as “important” or “very important” to growth, compared to 61 percent of respondents from advanced economies. Nevertheless, in emerging economies infrastructure investment has been trailing economic development and is now slowing their potential output growth.7 One way to generate growth is to bolster private sector participation through concessions and public private partnerships.8 Improving capacity and quality in both transport and energy connectivity also will generate growth.

PROMOTING INCLUSIVE GROWTH

Despite growth in the Asia-Pacific region, income disparities between the rich and poor have widened, and the benefits of growth have been distributed unevenly within and across member economies. Women, older workers and some minorities, as well as micro-enterprises and SMEs, have benefited disproportionately less from economic growth. In emerging economies, the 2015 State of the Region Survey shows that the starting point in promoting inclusive growth is to reduce corruption, rated “important” or “very important” by 87 percent of respondents. Over 85 percent of respondents from emerging economies rated as “important” or “very important” the provision of support to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Reforms in education and training came next in the Survey results from respondents in emerging economies, at 81 percent. Education reform to promote inclusive growth starts with improving the availability and quality of early, primary, secondary and tertiary education for the entire population, making sure that disadvantaged groups are included.

INCREASING FORMAL SECTOR EMPLOYMENT

A key challenge faced by emerging economies is the relative preponderance of jobs in the informal sector. Hiring and firing costs in the formal sector tend to be high, and trap vulnerable groups such as women and youth into involuntary informal employment. For these economies, structural reforms that foster entrepreneurship can create formal sector jobs for members of vulnerable groups, because young firms create a disproportionately large number of jobs. An OECD study has found that small firms in existence for five years or less account for 17 percent of employment yet contribute to around 42 percent of job creation.

Enhancing wage and working hour flexibility is another way to bolster the creation of formal sector jobs. Combining wage and working hour flexibility with improved social insurance coverage for laid-off permanent workers is one way to bring members of disadvantaged groups from informal to formal sector employment. In addition, high hiring and firing costs may discourage companies from innovating or adopting technologies, slowing down their economies’ progress.11 In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, among respondents from emerging economies, over 62 percent were “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied” with wage and working hour flexibility, and nearly 50 percent reported the same satisfaction levels as regards freedom to hire and dismiss employees.

Developed economies experiencing low productivity growth despite strong investment in knowledge-based capital stand to benefit from improved innovation policies. For these economies, productivity growth lies in incremental R&D tax incentives plus closely evaluated grant programs.12 For emerging economies, innovation related reforms to generate growth include increasing and reforming public support for R&D and improving the targeting of grants.13 The international mobility of skills and labor also can bolster innovation if policies are targeted at needed professional qualifications. In the 2015 State of the Region Survey, half of respondents from advanced economies reported that they were “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied” with skills and labor international mobility in their economy. Among respondents from emerging economies, satisfaction was even less, at 58 percent either “not at all satisfied” or “slightly satisfied.”

Inclusion of rural populations in overall growth can be boosted by infrastructure improvements that connect rural areas with urban centers. The 2015 State of the Region Survey results underscore the importance to inclusive growth of structural reforms that improve connectivity for rural areas, rated “important” or “very important” by over 80 percent of respondents from emerging economies.

Tax reforms that bolster the efficiency of tax systems can also foster inclusion through steps such as combating tax evasion and widening the tax base. Tax reform can lessen disincentives for women to return to work after giving birth by, for example, pegging tax allowances to the second earner’s income level and conditioning childcare support on returning to work.14 In the Survey, 66 percent of respondents from emerging economies viewed progressive tax policies as “important” or “very important” to inclusive growth, compared to 61 percent of respondents from advanced economies.

BOX 1: China’s economy: ups and downs, but still positive and promising

Contributed by CNCPEC

Since July-August, certain indicators of China’s macro-economy have shown a slip or fluctuation. In August, the stock market experienced unusual fluctuations. And then the Chinese currency depreciated. There have been reactions in the world market. What happened to the Chinese economy? Is China’s economy in deep trouble?

How to view the 7 percent growth?

The Chinese economy is in the state of a ‘new normal.’ That means it is going through a transition with traditional drivers being replaced by new ones. The extensive model of growth in the manufacturing sector is giving way to more intensive production. And over-reliance on investment is abandoned for greater balance between consumption and investment. This is a painful and challenging process. Ups and downs in growth are hardly avoidable, as they are natural in a period of adjustment and transition.

The Chinese economy is deeply integrated into the global market. Given the weak growth of the global economy, China could not stand unaffected. However, given the slowdown in global growth, the 7 percent growth China achieved in the first half of the year is not at all easy, and China’s economy is still within the reasonable range.

First, we are talking about a US$10 trillion economy, for which 7 percent growth actually generates more increase in volume than the double-digit growth in the past. And the 7 percent growth is in fact among the highest of the world’s major economies.

Secondly, in the first six months, 7.18 million new urban jobs were created, which means 72 percent of annual target has already been met. Surveyed unemployment rate in big cities was around 5.1 percent. Per capita disposal income grew by 7.6 percent, faster than the economy, with the income of rural residents growing faster than that of urban residents. As a result, consumers now have more money in their pockets to spend. Last year 100 million Chinese people travelled abroad. For the first half of this year, there was an increase of 16 percent compared to the same period of last year. Price levels have been kept basically stable.

Thirdly, China’s steady economic development has also benefited the world. China contributed about 30 percent to global growth in the first half of the year. With commodity prices dropping markedly on the global market, the growth of China’s foreign trade volume is slowing down. Nonetheless, the actual amount of commodities China imported has continued to go up; grain by 24.4 percent, copper ore 12.1 percent and crude oil 9.8 percent.

What is more encouraging is that China’s economic structure is rapidly improving. Today, the services sector already accounts for half of China’s GDP, and consumption contributes 60 percent to growth. Growth in high-tech industries is notably higher than the entire industrial sector; for the first eight months of this year, there was 14 percent increase compared to the same period of last year. Consumer demands for information, cultural, health and tourism products are booming. Energy conservation, environmental protection and the green economy are thriving. New economic growth areas are rapidly taking shape.

How to solve financial risks?

The ups and downs of stock markets are caused by the very nature of such markets, and the government normally does not intervene. The role of the government is to maintain an open, fair and impartial market order, protect the lawful rights and interests of investors, especially small- and medium-scale investors, promote the stable growth of the stock market in the long run, and defuse massive panic.

The recent unusual fluctuations in the Chinese stock market were mainly the result of previous rapid surges and big fluctuations in the international market. The Chinese government has taken some measures to defuse panic in the stock market and avoid systemic risks.

Such steps have proved successful. And similar steps have also been taken in some mature foreign markets. After a mix of stabilizing steps have been taken, the market has entered a stage of self-correction and self-adjustment. To develop the capital market is a key goal of China's reform, which will not change just because of the current fluctuations in the stock market.

Since the beginning of the year, China has deepened market reform in finance, taxation, investment, financing and prices. China adopted a host of measures to lift restrictions on market access and promote fair competition. Meanwhile, China is stepping up risk management to make sure that no regional or systemic financial risk will occur.

The high savings rate and large foreign exchange reserves mean China has ample financial resources. What is important is to channel the financial resources into the real economy. Recently, China has taken a number of reform measures as it cut interest rates and the reserve requirement ratio. Going forward, China will continue to ease restrictions on the access of private capital to the financial sector, and actively develop private banks, financing guarantee and financial leasing to better support the real economy.

Why depreciate RMB by 4 percent?

China has been working to improve the market-based RMB exchange rate regime. Recent measures to improve the quotation of the RMB central parity is a case in point, as it gives greater say to the market in deciding the exchange rate.

Given the complexities in the current international economic and financial conditions and the apparent divergence in market makers' expectations of the future trend of the RMB exchange rate, there had been a long-standing gap between the central parity and market exchange rate of the RMB. With improvements to the quotation of the RMB central parity, the RMB central parity will better respond to supply and demand in the foreign exchange markets, and systemically avert the sustained large gap between the RMB central parity and market exchange rate.

Since the quotation of RMB central parity was improved on August 11, initial progress has been made in correcting the deviation. Given the current economic and financial conditions at home and abroad, there is no basis for sustained depreciation of the RMB. Reform of the RMB exchange rate formation regime will continue in the direction of market operation.

China put forward the goal of convertibility of the RMB under the capital account back in the early 1990s. Over the past 20 years and more, China has been working toward this goal. Currently, there are only very few transactions that are still banned under the RMB capital account. China is advancing the convertibility of the RMB under the capital account in a steady and orderly manner.

Why a drop in China's foreign reserves?

There has been a recent drop in China's foreign reserves. This mainly reflects improvement to the mix of local currency as well as foreign exchange assets and liabilities of domestic banks, enterprises and individuals. There are three main reasons: first, some assets in foreign exchanges were transferred from the central bank to domestic banks, enterprises and individuals, including an increase of US$56.9 billion in the balance of foreign reserve deposits of domestic banks in the first eight months of this year, with a US$27 billion increase in August alone. Secondly, outbound investment by domestic enterprises has grown rapidly. Thirdly, domestic enterprises and other market entities are reducing foreign financing steadily, which helps reduce risks including high leverage operation and currency mismatch.

These changes are normal capital flows, which are moderate and manageable. Foreign investors who aim at long-term investments are still investing in China. For the first eight months this year, actual foreign investment to China was US$85.3 billion, 9 percent increase from the same period of last year. China's foreign exchange reserves remain abundant and are still very large by international standards. With improvement to the RMB exchange rate regime and progress in RMB internationalization, it is quite normal that China's foreign reserves may increase or decrease.

How about the future?

China is optimistic that its economy is on the right track and its future will be even brighter. This is based on the following two basic facts:

First, the Chinese economy is resilient and full of potential. China is going through the process of a new type of industrialization, IT application, urbanization and agricultural modernization, which all serve to mobilize the whole society and generate a strong force driving development and domestic demand. It is estimated that China’s domestic consumption expenditure will reach US$10 trillion by 2025.

Secondly, the ongoing structural reform is constantly delivering benefits. China is comprehensively deepening reform, accelerating structural reform and pursuing an innovationdriven development strategy to fully unleash the potential of economic growth. For China to advance structural reform, it is important to promote mass entrepreneurship and innovation. This makes up a major component of China’s ongoing structural reform and adjustment. Over 10,000 new market entities are being registered daily on average since last year. Measures have been taken to streamline administration, delegate government authority, strengthen regulation and improve services. The industrial upgrading will expand the import of advanced technology and equipment.

In sum, the above figures and facts serve to emphasize that the Chinese economy is still within the reasonable range despite the many difficulties and downward pressures, and China is not a source of risks for the world economy but a real source of strength for world economic growth. Although we have seen a slip or fluctuation in certain indicators over the past months, the policies and measures adopted in the previous stage are starting to pay off, and positive factors are building up in the economy, hence the upward trend in certain indicators. The fundamentals underpinning a stable Chinese economy have not changed. The ups and downs in the economy may have formed the shape of a curving wave, but the underlying trend remains to be positive. The Chinese economy will not head for a “hard landing.” After China succeeds in its economic transformation and upgrading, it will enter into a steadier, more quality-driven and more sustainable development stage, thereby playing a better role as an engine of world economic growth.

BOX 2: The United States economy: a locomotive for the global economy

An edited and abridged version of remarks by Dr. Charles E. Morrison at the 23rd PECC General Meeting

The overall picture on the United States economy is positive but not without uncertainty. On the domestic front the US economy is looking quite good, but with areas of fragility. There also are difficult headwinds in the global economy which have been reflected in recent stock market volatility in the US. The early stages of the 2016 presidential election add political to economic uncertainty. Over the longer term, strong basic institutions; continuing immigration of human talent from all over the world; and a virtuous relationship between government, business and the academic world are factors that contribute to the resilience of the US economy and will keep it at the forefront of the global economy for years to come.

Domestic drivers remain wellsprings of growth

In recent months the Federal Reserve has been grappling with whether to move ahead and increase the bank borrowing rate in the United States. In the summer of 2015, it seemed almost certain that the Fed would be moving ahead, but a change of policy has been delayed. Part of this dilemma is the impact that a rise in US interest rates would have around the world including in China, which has become a very important partner to the economies of the region. China’s slowdown also impacts the US, although less so than for most other economies. Exports account for only 13 percent of US GDP, and exports to China are only 7 percent of those exports. Domestic drivers remain overwhelmingly the wellsprings of economic growth.

GDP growth in the US in the second quarter was at 3.7 percent on an annualized basis. It followed a weak first quarter, and it is an upward revision of the preliminary figure, but it looked pretty good. Consumer spending was up 3.1 percent as people were buying homes, cars, and appliances, perhaps in anticipation in higher interest rates. Inventories did increase, but this was relatively small, and a larger figure reflected corporate investment in capital goods.

Consumer confidence also is positive. The University of Michigan index of consumer sentiment has been over 90 for the past nine months, the longest period since 2005. The late August figure was only slightly off. The Conference Board confidence index also has looked good, although there are other measures of economic confidence that are less rosy.

Employment and labor

One reason for greater consumer confidence and spending has been an improved job market. The August figure for unemployment was 5.1 percent, almost within the range of full employment. Employment has grown for 66 successive months, the longest on record, bringing unemployment down from 10 percent at the height of the recession. But there are weaknesses:

First, questions about the quality of jobs. Wages have not increased commensurately with hiring, only 2.2 percent over a year ago. There has been no strong indication of rising labor costs yet. In fact inflation is very low – the cost of living is only slight above last year and far below the Fed’s 2 percent target figure. If energy and food is taken out, the figure is healthier. Full employment should involve low unemployment and strong upward pressure on wages, and the latter is not the case.

Second, if we consider the broader measure of those not actively in the labor market but still wanting jobs and those in part time employment but wanting full time work, then the under-employment rate is about 10.5 percent. And the figures for un- and under-employment are much higher for minorities and young people, especially young blacks.

Third, labor’s share of income has continued its long-term decline – down 70 percent since World War II.

Housing and other economic sectors

The housing market situation looks much improved, perhaps reflecting low interest rates and pent up demand. New housing starts are up 20 percent over last year and are the highest since the GFC. But it is still only half the level of the 1990s, and much comes in the form of apartments rather than single family houses, which have more economic impact. Resales of existing homes are high, but first time buyers account for just 30 percent whereas some believe that 40 percent would be an appropriate figure for a robust economy. Prices have risen faster than the ability of young, first time buyers to buy which, along with minority unemployment, is a sign of growing equity issues.

As for other sectors, construction is doing very well, at the highest level in seven years. Car sales are very strong, but manufacturing is at its weakest in two years. This reflects the layoffs in the energy industry, and there may be some additional downturns coming in that sector.

The external sector

Exports are not doing well. The dollar is strong, and President Obama’s export doubling plan of a few years back went nowhere. As reflected in the debate on the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), publics remain very suspicious of globalization and trade agreements. The political debate on trade will be replayed in the approval process for the TransPacific Partnership, probably with an outcome almost identical with the TPA. As the TPP involves many economies already with free trade agreements with the United States – with the notable exception of Japan - the actual economic impact of the current TPP, as opposed to its longer-term significance as a benchmark for later deeper trade agreements, will be limited.

Politics adding to uncertainty

Turning to government, the political will for stimulus at the beginning of the GFC dissipated quickly, and reduced government spending, reflecting budget compromises between the Administration and Congressional Republicans was a drag on economic growth. Similarly state and local governments were cutting expenditure and jobs. While government is no longer much of a drag compared to 2-3 years ago, there is virtually no fiscal stimulus for the economy.

Because of both economic and political uncertainties, the Fed has continued to delay increasing interest rates. The objective of the Fed is to return to more normal rates, but it is a cautious and conscientious institution and is still waiting further signs of robustness in the US economy.

What is the “new normal?”

The uncertainties in a broader sense reflect a lack of a clear understanding not just about the US economy but what the “new normal” really is in the global sense. For example, what does “employment” mean today compared to the past? In the US, perhaps almost a third of those in the labor force are part of the “1099 economy”, that is consultants and individual contractors rather than company employees in the traditional sense. These may be Uber drivers, real estate agents, Air BnB operators, and maintenance and health workers, for example, with a very different kind of work experience and typically reduced benefits from the past. Is this the future of work?

And are we in a period of “secular savings stagnation” in the advanced economies where investment and savings are simply not aligned. What would be the policy implications of that if savings surpluses and low interest rates are a part of the future for years to come?

In conclusion, the US is a locomotive, maybe the only accelerating locomotive in the global economy, even if the acceleration is somewhat sluggish, irregular, and of uncertain duration. But in spite of some uncertainties, the US remains a main and leading actor in the global economy and will be for years to come. First, its basic political and economic institutions, including the Fed, are very strong. Second, there remain high rates of immigration that refresh society and abate the effects of demographic aging, a headwind affecting many advanced and even emerging economies. Almost 50 million of the 320 million Americans were born overseas – a much higher rate than other major economies. There is continuous circulation through our society. Third, strong educational institutions, and a unique and virtuous relationship between government, business, and the academic world, most famously seen in Silicon Valley, foster continuing innovation in the US economy.